A question of image (1)

Review of the exhibition catalogue: “Juliette Récamier, muse et mécène” (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, 27 March – 29 June, 2009)

One of the strong points of the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition “Juliette Récamier, muse et mécène” (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, 27 March – 29 June, 2009) is the detailed commentaries and descriptions of each of the 170-odd works on display. But there are others as well. It is beautifully and richly illustrated and offers the reader a great deal of information regarding the life of Juliette, including the well-known episodes such as her relationship with François-René de Chateaubriand and the story behind the famous painting by Jacques-Louis David. Next to these famous aspects of her life, the catalogue also recounts the lesser-known episodes, which help us to understand a little better the at times mysterious Madame Récamier.

“Lyonnaise” and proud of it

As is appropriate for this lady from Lyon, the exhibition takes place in her hometown, and the catalogue goes to great lengths to highlight the strong attachment she felt for the region. Indeed, Juliette's bequest to the city demonstrates just how important it was to her.(1) This devotion was reciprocated: Edouard Herriot (1872-1857), mayor of Lyon and President of the Assemblée Nationale, wrote a biography of her life, and both a street and a high school are named after her. The staff-room of the latter even features a copy of the bust, sculpted by Joseph Chinard (1756-1813).

"Directory-style" and consular sumptuousness

It is likely that Juliette first met Chinard around 1790. From very early on, she benefitted from a thorough artistic education, before being taught to paint by Hubert Robert (1733-1808). Throughout her life, she took great pleasure in visiting the artists' workshops, and her taste for the arts was made manifest in the interior design of her home, a town-house on Rue du Mont-Blanc that she bought in 1798.

The results were everything that the couple could have hoped for: infused with “anacreontism” (2), the Récamier town-house displayed “Directory-style” at its apogee. The catalogue highlights the influence that this style had on subsequent decorative fashions and on architects and designers, including Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841), who designed Queen Louise's chambers in the Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin. The richness on display in Juliette's home reflected her husband's social status, who was made régent de la banque de France and held grand parties at the Château de Clichy and the Domaine de Rancy. The catalogue also details Madame Récamier's salon, where she entertained the great artists and politicians of the day, and her role as hostess. In 1802, with the Treaty of Amiens signed between England and France, Juliette's international status was confirmed during a triumphant journey to England. In 1806, however, her life was turned upside down: her husband was ruined and the years of luxury came to an end.

The Bonapartes and exile

This change in fortune was accompanied by the imperial regime's increasing suspicion towards Juliette. Her relationship with the Bonaparte family began well enough, with Juliette receiving the amorous attentions of Lucien Bonaparte. However, these feelings were not shared, and relations between the Récamiers and the Bonapartes became steadily worse due to Juliette's friendship with Germaine de Staël (1766-1817), a political opponent of Napoleon whom she had met in 1798. In 1807, Juliette spent some time at de Staël's Château de Copet, in Switzerland. Their close friendship is clear from a comment made by de Staël, delighted with a dress given to her by her younger companion: “I shall tell everyone that it is from you, and all the men shall sigh that it is not you who is wearing it.”(3) Napoleon could not tolerate such a relationship, and in 1812, Juliette was exiled.

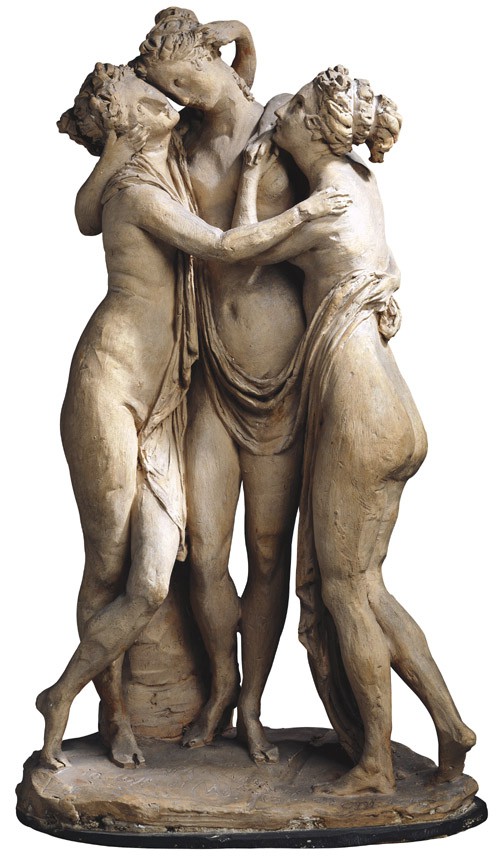

As well as items that demonstrate the richness available in French collections, the exhibition features a number of items from Italian collections which date from Juliette's exile, a part of which she spent in Italy, in 1813 and 1814. The King of Naples, Joachim Murat (1767-1615), even organised a special excavation in her honour at Pompeii. It was during this time that Juliette met the famous Italian painter, Antonio Canova (1757-1822). Perhaps a little enamoured of her, Canova offered her one of his works entitled “The Three Graces”. Their relationship took a slight knock however when the artist presented Juliette with a sculptured bust of her, created from memory. Now known as “Juliette Récamier as Beatrice”, Juliette was unable to see herself in the piece, and with good reason: the artist had idealised her, giving her a Greek profile. This slight blip was not enough to seriously damage their friendship.

A collection based on friendship

The study of Juliette's close-circle is partly a study of her sociability, and partly a study of her friendships. Her choice of art, and what went into her collection, was more often than not guided by her friendship with the artist or the models involved, rather than artistic “taste” at the time. That is not to say that there is no sense of that in her collection, but rather that the arts represented for Juliette a reminder, a souvenir, of her friendships and relationships with those close to her.

The exhibition, to its great merit, attempts to reunite many of Juliette's favourite pieces, notably basing its organisation on her will and an inventory of her keepsakes, distributed after her death by her niece Amélie Lenormant. It should also be noted that the exhibition has been thoughtfully conceived; indeed, no major work of art linked to Juliette has been forgotten (although unfortunately the portraits by François Gérard and David as well as the original furniture from Juliette's bedroom(5) could not be moved). The exhibition even looks beyond the figure of Madame Récamier, with its gallery of personalities and muses from the period. Commentaries and descriptions narrate this detailed and interesting gallery, and audio-guides (in French) are available for no extra cost, something that should be recognised. This attempt to cover absolutely everything does however result in one or two attribution problems(6), and an occasional lack of space to really appreciate the works on display.

A queen of fashion

The exhibition is perhaps at its most intimately accessible when considering the section dedicated to Juliette's sartorial possessions. On display are perhaps the most beautiful exhibits of the collection, including shoes, dresses and accessories from the period, the majority of which have been loaned by the Musée Galliéra. In an intelligent stroke of exhibition conception, the clothes on display on the ground floor can be admired from every conceivable angle, up on the first floor. Juliette took advantage of the relaxing in clothing fashions which occurred towards the end of the 18th century: the modern woman could enjoy greater freedom of movement.

Madame Récamier favoured white cotton dress-robes, as well as a hairstyle that many of her contemporaries described as “bizarre”, and generally avoided diamonds, preferring pearls. The cashmere shawl that she wore to dances became intrinsically linked with her. Amélie Lenormant remembers how “she had a passion for dance and, early on, she made it a question of honour that she be the first to arrive at the ball, and the last to leave.”(7) Madame Récamier went on to dictate fashion tastes, and a drawing of her appeared in the 6 November, 1802 edition of the Journal des dames et des modes.(8) Jehanne Lajaz notes that “Juliette was not simply fashionable; she had a style, indeed, she was simply stylish” and was already heralding the birth of “the Romantic movement's aesthetic cannon”.

A question of image (2)

Juliette was very preoccupied with her image, particularly coming from a family of the “haute bourgeoisie” which was once again able to private commission portraits following the revolutionary years. She was just twenty-one when she served as a model for the bust sculpted by Chinard. She would go on to become one of the most admired, and one of the most depicted, women of the period, but very few of these works won her attention. Her contemporaries, even her friends, rarely acknowledged the 'divine' in their images. Was it merely that none of the artists was up to the task of portraying her beauty, or was it simply difficult to depict a physiognomy that was reputed to be highly 'changeable'?

"A visual cacophony"

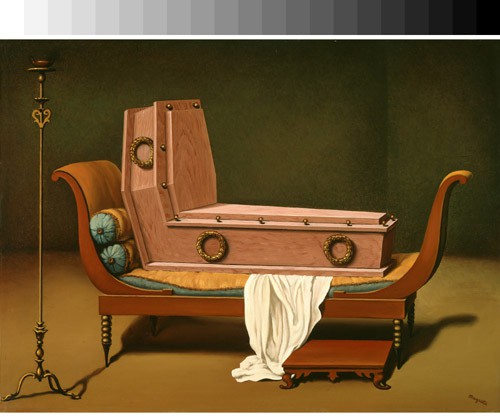

And what if Juliette herself was at the root of this visual cacophony? Refusing to be 'captured' by the artist would certainly be one way of maintaining the aura of mystery about her… Stéphane Paccoud, the commissaire général for the exhibition and the 19th century paintings and sculptures curator, describes Madame Récamier as “a real strategist [when it came to] the control of her image”. One wonders what she would have thought of Gaston Ravel's film about her from 1928, which actually features in the final section of the exhibition. Juliette and her influence continued to haunt her period and those that followed her (particularly the works by René Magritte). Driven partly by ornaments and trinkets, her presence is still keenly felt in the public's subconscious. She even featured on the 12 franc stamp, released in 1950, which was based on the painting by François Gérard.

And what if Juliette herself was at the root of this visual cacophony? Refusing to be 'captured' by the artist would certainly be one way of maintaining the aura of mystery about her… Stéphane Paccoud, the commissaire général for the exhibition and the 19th century paintings and sculptures curator, describes Madame Récamier as “a real strategist [when it came to] the control of her image”. One wonders what she would have thought of Gaston Ravel's film about her from 1928, which actually features in the final section of the exhibition. Juliette and her influence continued to haunt her period and those that followed her (particularly the works by René Magritte). Driven partly by ornaments and trinkets, her presence is still keenly felt in the public's subconscious. She even featured on the 12 franc stamp, released in 1950, which was based on the painting by François Gérard.

How can such a myth surrounding Madame Récamier have been constructed, and moreover, how can it have endured for so long? The secret is perhaps in her constancy: in the image of virtue that she exhibited, unlike that of the so-called “merveilleuses”(9) who were often considered frivolous by their contemporaries; and in her taste for the Directory style, as much in her interior design as her dress. Madame Récamier was and remains a representative of the arts under Napoleon: this “dame au sofa”, this languid sylph, still continues to inspire adoration in artists and the general public alike.

Elodie Lerner (tr. & ed. H.D.W.)

Publication details

Click here for our commentary on the portrait of Madame Récamier by David and here for our section on Napoleonic fashion.

François Gérard's portrait of Madame Récamier featured in our first Fondation Napoléon atelier, which was on the masterpieces of the Napoleonic art.

Exhibition catalogue: “Juliette Récamier, muse et mécène” (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, 27 March – 29 June, 2009)

Place and date of publication:

Paris, 2009

Publisher:

Hazan

Number of pages:

271 pages